UNIVERSEUM annual meeting XX – Brno/Prague Czech Republic – 19-21 June 2019

By Sarah Gambell, PhD candidate Information Studies, University of Glasgow

As someone who deals almost exclusively with the digital realm in day-to-day research, often traditional museological practice, as it involves collections can be more difficult to integrate with. Tangible, analog, haptic representations of arts and artefacts are certainly of great importance, but I deal with what has been destroyed – the intangible, born digital, missing heritage. Coming in to the annual meeting this year, I naturally gravitated towards any mention of the use of digital in a museum context, and I was not left disappointed. In the lead up to the meeting, I was particularly drawn to subtheme two developed by the organisers at Masaryk University: “New media and their role in the participatory curation and interpretation of academic heritage” – how can museums better use and integrate digital tools in their collections and effectively communicate to their audience?

My research interests focus on the reconstruction of cultural heritage that has been displaced or destroyed as a result of conflict; as I focus primarily in the Middle East, it is often tied to geo-political disruption, and looting and violent destruction of heritage sites as a result. How does one go about ensuring that the few records we have of these artefacts or sites has a life and presence post-conflict? For this, we turn to digital – 3D reconstructions, virtual reality, and augmented reality. Crowdsourcing tourist photos of heritage before destruction to process through photogrammetry software, giving public platforms to the public to upload 3D visualisations that are publicly accessible, and with limited copyright restrictions. This is obviously only a minute part of what goes into the field, but the ripples are felt far and wide in the museums’ sector, particularly relating to how the audience will perceive it: If heritage is only available in digital form, will audiences still connect with it? How does a museum ensure that the visualisation is publically accessible as widely as possible? What kind of sustainability plan or data management plan can be expected?

University of Antwerp’s Daniël Ermens presentation, “Collective Memory: engaging the academic community using new media”, evoked what might be possible when interactive website that would tap into the collective memory associated with the collections. Continually adding information where it might be absent – rebuilding the lost context.

Janet Liadla, of the University of Tartu evaluated through her research who might museums best explore the use of virtual and augmented reality in order to innovatively connect the audience with the collections. Similarly, Alison Hadfield, of St. Andrews, also looked at a case study evaluating audience connections with interpretive formats, including 3D visualisation and digitisation. These connections with the digital artefacts were juxtaposed with findings from haptic handling sessions. Her findings suggested that multisensory experiences improved user connections with the artefacts.

Janet Liadla, of the University of Tartu evaluated through her research who might museums best explore the use of virtual and augmented reality in order to innovatively connect the audience with the collections. Similarly, Alison Hadfield, of St. Andrews, also looked at a case study evaluating audience connections with interpretive formats, including 3D visualisation and digitisation. These connections with the digital artefacts were juxtaposed with findings from haptic handling sessions. Her findings suggested that multisensory experiences improved user connections with the artefacts.

Working with digital is certainly not without its setbacks and complications; often it’s a very expensive venture, there are issues of obsolescence, copyright and intellectual property rights could contrive a headache, to name a few. All roadblocks, as in normal museological practice, have their means for mitigation. They may just need some new approaches.

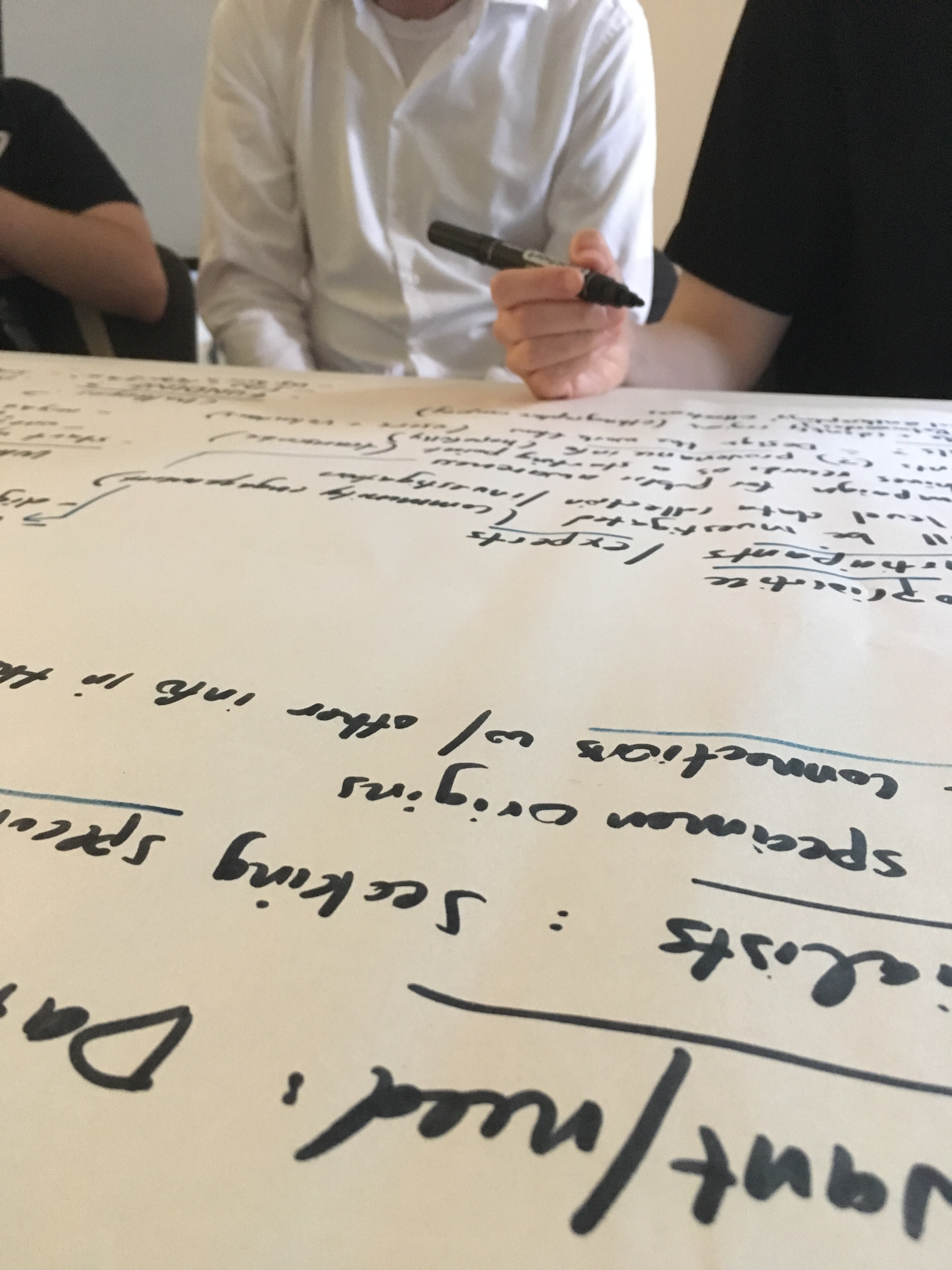

Day three of the annual meeting brought the working groups, where those interested in databases were able to break off and discuss crowdsourcing and community generated heritage. Although the case studies in this session did not deal with lost heritage, it did emphasis rebuilding a lost context. Community generated content is an invaluable tool for seeking outside of the professional realm experts in a particular subject which may be in danger of drifting from the collective memory. Establishing a database, or interactive site where recounting, stories, verified and moderated facts can be curated in a step on bringing a community together around a collections or artefact. Raising the public interest and awareness of heritage that may be close to them is the best way to ensure it is continually accessible; more so than simple digitisation.

While during the working group we were not able to solve all of the issues related to crowdsourcing information related to heritage, we left with a room full of people much more confident in undertaking a project like this in their own universities or organisations.

While during the working group we were not able to solve all of the issues related to crowdsourcing information related to heritage, we left with a room full of people much more confident in undertaking a project like this in their own universities or organisations.

As we patiently await, (or rather impatiently) next years’ meeting in Belgium, I hope that we all can begin to think more about how digital representations of heritage might find their way into collections with tangible heritage and further enhance public engagement with the collections we know inside and out –